PDF: The (Deceivingly) Simple Format

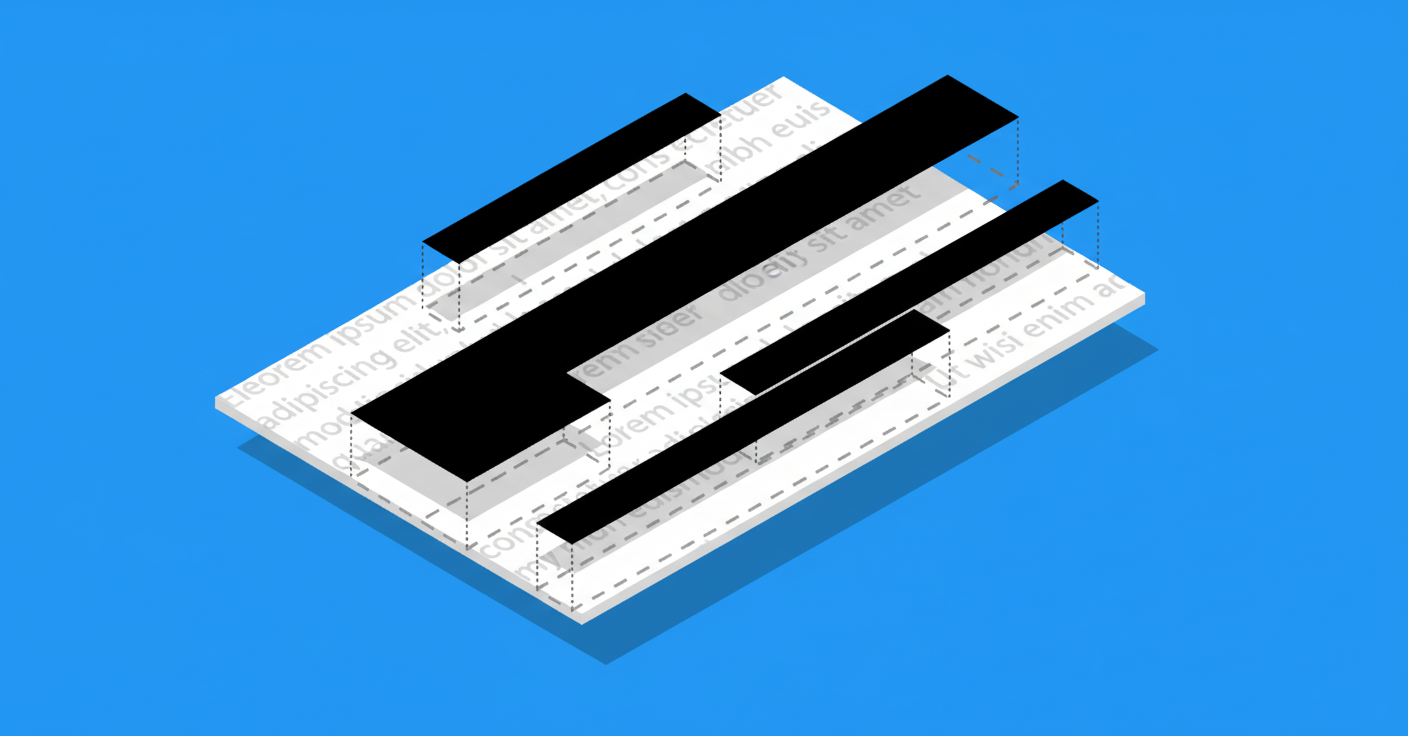

Understanding PDF internals is key to seeing how redactions go wrong. A PDF file isn’t a simple flat image – it’s a multi-layered document that can contain text, images, vector graphics, annotations, bookmarks, metadata, and more, all possibly coexisting. Redaction failures usually stem from leaving one of these layers or components intact. Below we break down common failure points:

Masking Instead of Removing (Visual vs True Redaction)

The number-one redaction mistake is adding a black box or opaque highlight over sensitive text without actually deleting that text from the PDF. This creates a fake redaction – the content looks hidden, but it’s still in the file. Since PDF viewers render content in layers, an overlay annotation can sit on top while the text layer beneath remains untouched. An attacker can simply select the “hidden” text and copy-paste it into another document to read it.

This is exactly how journalists uncovered confidential details in the Paul Manafort court filings and other cases – the lawyers had placed black bars over text, but a quick copy-paste revealed everything underneath. Flattening the PDF (merging layers) after drawing black boxes might sound like a solution, but even that can be insufficient if it doesn’t remove the underlying text. In some cases, flattening just merges the black shapes into the page content but still leaves the original text data, making it copyable in the merged layer. The only cure here is true removal: the sensitive text must be excised from the PDF’s content stream, not merely hidden.

Hidden Text Layers (OCR and Invisible Text)

PDFs can contain hidden text that isn’t visible to the reader but is embedded for search or accessibility. A common scenario is scanned documents that have been OCR-processed: you see a scanned image of a page, but an invisible text layer sits behind it to allow text search. If one redacts such a document by drawing a black box on the image of the text, the image is obscured – but the invisible OCR text underneath may still contain the words. Unless the redaction process also removes or updates that text layer, the supposedly redacted info can still be extracted via search or copy.

Proper redaction tools are aware of this; they should redact both visible content and any hidden OCR text in that area. Another example of hidden text is content hidden via PDF form fields or scripting (e.g., a form field with text that’s not visible). If not sanitized, that text remains. Bottom line: Redaction must account for all text layers. Failing to remove an OCR layer or any unseen text will result in a redaction failure.

Annotations and Comments

PDF annotations (comments, sticky notes, markups) can inadvertently carry sensitive data. Sometimes people attempt redaction by adding a comment or note (for example, writing “[REDACTED]” as a note) or they use a redaction annotation feature but never apply it. Redaction annotations in tools like Acrobat are essentially pointers that say “remove this content” – but until you apply them, they themselves might store the text to be removed. If left unapplied, those annotations could be extracted.

There have been cases where improper use of Acrobat’s redaction left behind metadata or “sticky notes” where the black box was, which still contained the text or a reference to it. Additionally, standard PDF comments might mention the sensitive info (e.g. an editor leaving a note like “This paragraph mentions John Doe, redact his name”). If those aren’t deleted, someone inspecting the PDF can find them. Always ensure that any annotation used in redaction is flattened and removed – in Acrobat, this means confirming the redaction operation so the tool replaces the area with a black box and strips out the underlying content and the annotation markup.

Document Metadata

Metadata is data about the document (or elements within it) that is not shown in the main content. PDF metadata can include the document’s author, title, subject, keywords, creation and edit dates, the software used, and more. Critically, metadata fields might inadvertently contain sensitive info – for instance, the “Title” field might be a copied line of an internal memo that includes a name or case number, or an image XMP metadata could include a caption or photographer’s note that wasn’t meant to be public.

Even if you perfectly redact visible text, if you forget to clear metadata, you could leak information. Search engines and PDF tools can read this info easily. Worse, PDFs can store previously deleted content or revision history in metadata streams or as part of embedded object data. There have been instances where “deleted” text from an earlier draft was still embedded in the file’s metadata or incremental update history.

If an attacker inspects the PDF’s metadata (using a tool like ExifTool or even Adobe’s Document Properties dialog), they might discover names, document IDs, or hidden text that should have been redacted. Thus, failing to sanitize metadata is a common redaction failure. The remedy is to use a sanitize or “remove hidden information” function on the PDF after redaction, which scrubs metadata and other non-visible data.

Bookmarks, Links, and References

PDF bookmarks (the navigational table of contents often shown in a sidebar) and hyperlinks can also carry content that might not be obviously visible in the main text. A famous example occurred in a publicly released contract between the EU and AstraZeneca: the document was appropriately redacted in the body, but the PDF’s bookmarks (which listed section titles) still contained the redacted terms – in this case, a financial figure that had been obscured in the pages was plainly visible in a bookmark title. This oversight meant anyone could click the bookmarks or inspect them to see the “hidden” number.

Hyperlinks are another risk: a hyperlink has two parts – the text you see, and the URL or destination hidden underneath. If a hyperlink’s visible text is redacted but its URL still contains sensitive info (for example, a URL with someone’s name or an account number), that info remains in the file. Or a link could lead to a file path on a local drive revealing a person’s name or project code. Redaction processes need to account for these by either removing or updating bookmarks and hyperlinks that reference removed content. If not, attackers will check these sections of the PDF for any giveaway text.

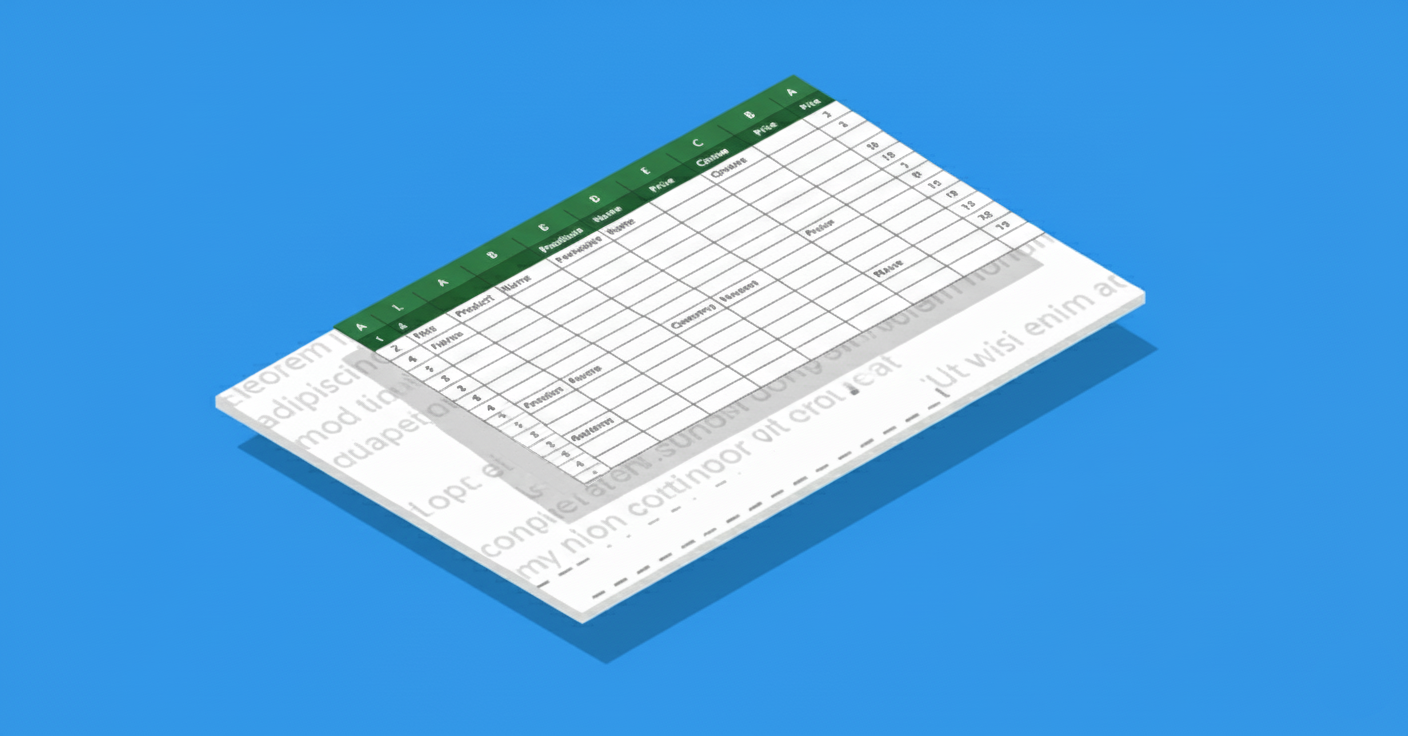

Embedded Files and Images

PDFs can embed attachments or files (like an Excel spreadsheet, or a text file, included within the PDF) and can contain images that have their own metadata. If you simply redact the PDF’s pages but do not remove embedded attachments, you might be handing an attacker the raw data on a platter. For instance, say a PDF has an embedded Excel file for reference, and you obscured a table in the PDF. If the Excel is still attached and contains the full data, the redaction is defeated by just extracting that attachment.

Similarly, images in PDFs can carry metadata (EXIF or XMP tags) that might include descriptive text. Perhaps you redacted a person’s face in a PDF image, but the image’s metadata still names them as the subject or has a comment like “Photo of [Name]”. That’s a hidden layer of data that needs sanitization. Always remove or examine attachments and scrub image metadata when redacting. Many redaction/sanitization tools will list and remove embedded files, but it must be explicitly done.

Incremental Saves and Cached Data

The PDF format supports incremental updates – meaning when you save edits, a PDF editor might append the changes to the file, leaving the original content in place (just marked as old). This is efficient for editing, but dangerous for redaction. For example, if you use a PDF editor to delete a paragraph and add a black box, then save incrementally, the PDF may actually contain both the old content and the new version. A savvy attacker could look at the PDF objects that are not active and find the removed text still lurking in the file’s data.

An improper redaction that doesn’t rewrite the file from scratch (or “save as”) can thus be undone by digging into the file structure. The proper approach is to perform a full save (sometimes called optimizing or sanitizing) so that no remnants of previous content remain. Many tools’ “Remove Hidden Information” features will eliminate such orphaned data, or one can use PDF optimization to discard deleted content. Failure to do so means the “deleted” text is recoverable with a bit of PDF forensics.

Partial Redaction or Overlooked Elements

Redaction is sometimes done in a hurry or via search scripts, and it’s easy to miss things. If only the first occurrence of a sensitive term is blacked out, but it appears elsewhere (even in an image caption or a footnote) and is left, that’s a failure. Commonly overlooked elements include page headers/footers that might contain repetition of a name or ID, file names printed on a page, or even auto-generated indexes.

For instance, a generated index or table of authorities in a legal brief might list a case name that you redacted in the body text. If you don’t update or remove the index, the name might still be readable there. This is less a technical failure than human error, but it underscores the importance of thorough review – the security of the redaction is only as strong as the weakest overlooked snippet. Always check all parts of the PDF (headings, footers, page numbers, indices, etc.) for the data you intend to redact.

Information Leaking from Redaction Marks

Even when content is properly removed, the redaction marks themselves can leak some information if not done carefully. For example, if you have a black box exactly covering a word, the length of that black box gives a clue to the word’s length (and potentially its identity). In one case, researchers noted that redacted names were guessed by matching the character width patterns of the blacked-out area. If a proportional font was used, the total width of a name (say “John” vs “Paul”) can differ, and an attacker with a list of candidates could brute-force which name fits in the redacted space.

Advanced attacks even exploit glyph spacing: a study found that tiny sub-pixel position shifts of characters in PDFs can leak letters of redacted text if those shifts remain after redaction. Essentially, even if text is removed, traces like the exact size of the redacted region or formatting artifacts can give hints. Mitigating this requires caution: some redaction tools intentionally randomize or standardize the size of redaction blocks or use a fixed-width font for any placeholder text to avoid width leakage.

In most typical scenarios, this level of attack is rare, but it’s a known risk. Key point: a perfectly secure redaction removes the content and any predictable clues about it. If the mere presence of a blacked-out 5-character-long gap would be problematic, consider replacing text with a generic length (e.g., “XXXXX”) instead of a tight box, or otherwise obscuring the exact length. For extremely sensitive cases, converting to an image (rasterizing) can help because the exact text metrics are lost – though as noted, even raster images can leak if the shapes of letters can be discerned. In practice, however, the bigger failures are leaving actual text or data in the file, which we’ve covered above.

Summary

In summary, PDF redaction fails when any instance of the sensitive information (or references to it) remains in the document’s visible or hidden data. This can happen through user error (using the wrong method) or by not accounting for PDF’s many data containers (text layers, metadata, etc.). Next, we’ll see how attackers or curious readers can exploit these failures to retrieve supposedly redacted data.